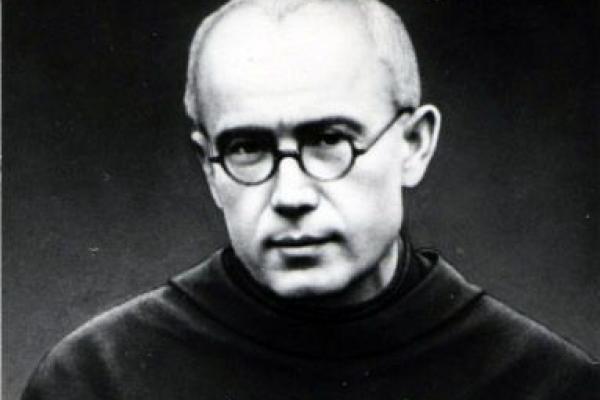

He began life on Jan. 8, 1894 as Raymond Kolbe, the second son of a weaver in a town called Zdunska Wola in Poland, near Lodz. As a boy, Ray, as he was known, showed a strong mischievous streak and had a penchant for getting into hot water.

That changed forever when a seemingly tiny incident became the pivot point of his life.

One day, Ray got caught in his usual antics, which elicited a scolding from his mother. The tongue-lashing deeply bothered young Ray. He was sad, not for the punishment, but because he had hurt his mother. Later, he wrote about the effect of the incident: "That night I asked the mother of God what was to become of me. Then she came to me holding two crowns, one white, the other red. She asked if I was willing to accept either of these crowns. The white one meant that I should persevere in purity, and the red that I should become a martyr. I said that I would accept them both."

Ray wasn't sure if it was a dream or a vision, but it didn't matter what he called the experience. Dream or not, the experience had a vivid reality to it, and it stayed with him the rest of his life. He saw the events of his life in terms of the white and red crowns.

When he was only 16 years old, Raymond Kolbe joined the Franciscans, taking the name Maximilian. As a Franciscan, he enjoyed a varied ministry, writing and publishing articles, teaching history in Poland, and building friaries in Warsaw; Nagasaki, Japan, and India. Then God began to fulfill young Ray's dream of Mary and the two crowns.

Our Lady, as it turned out, would be handing him the red crown.

In 1936, the Franciscans recalled Fr. Kolbe from Asia so he could supervise the Warsaw friary. The darkness of war, however, cast a long shadow over Europe and the world. Father Maximilian could see it coming. When Hitler invaded Poland in 1939, no one had to draw Fr. Maximilian a map. He knew what that meant. He knew that the Nazis would seize the friary.

Instead of fretting over this bad news, Fr. Kolbe went into action. He told his friars they were free to return to their homes, asking only a small number to remain behind to help implement a plan. Father Maximilian got the word out that refugees were welcome at the friary. Soon, the innocent victims of war made their way to the refuge. Thousands of people spent time with the friars, receiving shelter, food, clothing, and care. Some two-third of the refugees were Jews.

The Franciscans' works of mercy, though, drew the attention of the Nazis, and in May 1941, the government shut down the friary and sent Fr. Maximilian and four other brothers to the death camp at Auschwitz, Poland.

Amid this unsettling, he wrote home to his mother. In a letter dated June 15, he told her:

Dear Mama, At the end of the month of May I was transferred to the camp of Auschwitz. Everything is well in my regard. Be tranquil about me and about my health, because the good God is everywhere and provides for everything with love. It would be well that you do not write to me until you have received other news from me, because I do not know how long I will stay here. Cordial greetings and kisses, affectionately, Raymond.

Father Maximilian's" words hinting at a short stay proved prophetic. Two months later, he would be dead.

'Let me take his place'

In late July, a prisoner from Fr. Kolbe's barracks went missing. The Nazis presumed that he escaped. They invoked their standard rule in such cases: If someone escaped, 10 men from the same barracks would be killed in his place. The condemned would be locked in the starvation bunker, going without food and water until they died a long, tortuous death.

The prisoners from Fr. Kolbe's barracks were ordered to assemble before camp Commandant Karl Fritsch.

"You will all pay for this," Fritsch told the men. He then chose the unlucky 10. One of those was a man named Francis Gajowniczek. He broke down.

"My poor wife!" Gajowniczek screamed. "My poor children! What will they do?"

The men froze, not knowing how Commandant Fritsch would react. Father Maximilian walked forward to Fritsch, removed his hat, and told him, "I am a Catholic priest. Let me take his place. I am old. He has a wife and children."

Fritsch said nothing. He gazed at the priest for several seconds, before speaking.

"What does this Polish pig want?"

"I am a Catholic priest," Fr. Maximilian repeated. "Let me take his place. I am old. He has a wife and children."

The request was granted.

Years later, Francis Gajowniczek remembered the moment:

I could only thank him with my eyes. I was stunned and could hardly grasp what was going on. The immensity of it: I, the condemned, am to live and someone else willingly and voluntarily offers his life for me, a stranger. Is this some dream?

I was put back into my place without having had time to say anything to Maximilian Kolbe. I was saved. ... The news spread quickly all around the camp. It was the first and last time that such an incident happened in the whole history of Auschwitz.

Maximilian and the nine other men were immediately hustled to Building 13, the infamous starvation bunker. They were literally thrown down the stairs and locked in. Amazingly, an eyewitness account survives of what the men went through in the hole of Building 13. It came from Bruno Borgowiec, one of the prisoners assigned to service the death bunker.

'This priest is really a great man'

Borgowiec told his story before he died in 1947:

The ten condemned men went through terrible days. From the underground cell in which they were shut up there continually arose the echo of prayers and canticles. The man in charge of emptying the buckets of urine found them always empty. Thirst drove the prisoners to drink the contents. Since they had grown very weak, prayers were only whispered. At every inspection, when almost all the others were lying on the floor, Father Kolbe was seen kneeling or standing in the centre as he looked cheerfully in the face of the SS men.

Father Kolbe never asked for anything and did not complain. Rather, he encouraged the others, saying that the fugitive might be found and then they would all be freed. One of the SS guards remarked, "This priest is really a great man. We have never seen anyone like him."

Two weeks passed in this way. Meanwhile, one after another they died, until only Father Kolbe was left. This the authorities felt was too long. The cell was needed for new victims. So one day they brought in the head of the sick quarters, a German named Bock, who gave Father Kolbe an injection of carbolic acid in the vein of his left arm. Father Kolbe, with a prayer on his lips, himself gave his arm to the executioner. Unable to watch this, I left under the pretext of work to be done. Immediately after the SS men had left, I returned to the cell, where I found Father Kolbe leaning in a sitting position against the back wall with his eyes open and his head drooping sideways. His face was calm and radiant.

The date was Aug. 14, 1941.

Maximilian's remains were sent to the crematorium. No special notice was made of his death.

Except for the word of what he had done.

God's Will Be Done

The story raced through Auschwitz and into immortality. One survivor of the camp talked of what the news of Fr. Maximilian's sacrifice did for the prisoners, saying it was "a shock filled with hope, bringing new life and strength." He likened it to "a powerful shaft of light in the darkness of the camp."

Francis Gajowniczek lived to be 95 years old. Maximilian Kolbe bought him 53 years of life. When he returned to his hometown after being freed by the Allies from the death camp, Francis discovered that his two sons had died in the war. Only his wife survived.

Francis never forgot Fr. Maximilian. Every year on Aug. 14, he went back to Auschwitz, descended the stairs to Building 13, and prayed to the saint-priest.

The cell where the 10 men died has been preserved as a shrine. Perhaps the supreme irony in the sacrifice of Fr. Maximilian lies in the fact that the "escaped" prisoner had not escaped at all. He had drowned in a latrine. The officers of the camp did not bother to thoroughly check.

Father Maximilian had kept his word to Mary. He accepted both crowns: the white for purity and the red for martyrdom. Pope Paul VI beatified Maximilian Kolbe in 1970. Pope John Paul II made him a saint in 1981.

The Franciscan Friars of the Immaculate are a Franciscan reform begun at Frigento, Italy, in 1970. The follow the ideal and life of "Ray" Kolbe in their total consecration to the Immaculate Virgin.

Dan Valenti writes for numerous publications of the Marians of the Immaculate Conception, both in print and online. He authors "Dan Valenti's Mercy Journal" for this website.